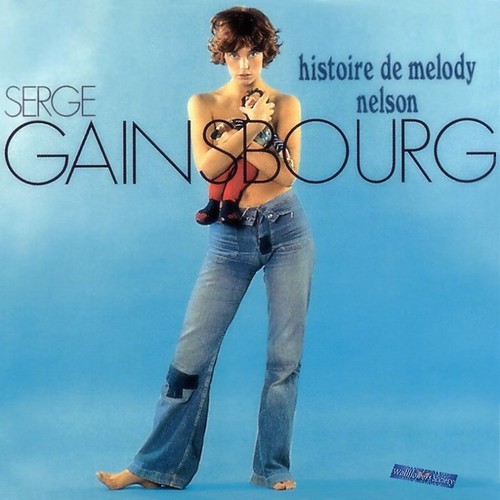

L'HISTOIRE DE MELODY NELSON by SERGE GAINSBOURG

Humphrey Bogart in Nicolas Ray’s In A Lonely Place (his best performance, bar none) is a tired and cynical writer who surely knows, even as he writes the story of his love affair with Gloria Graeme, that he is killing it; for when he finishes the script, the affair will die. Beauty must be tarnished. Bogart may or may not be guilty of a murder in that film, but it’s the suspicion that kills the love; hope is futile, in retrospect. And here is Serge Gainsbourg, whispering so close to the microphone as to be almost consuming it, delivering a tale of love as old as time and money, with glorious technicolour hindsight; with the voice of a man who knows bitterly that you can’t nototiate with that most twisted of iron councils, Fate.

‘Les ailes de la Rolls effleuraient des pylônes

Quand m'étant malgré moi égaré

Nous arrivâmes ma Rolls et moi dans une zone

Dangereuse, un endroit isolé’

(‘The Rolls' wings brushed against poles

When despite myself off my path

We arrived my Rolls and I in a dangerous

Zone, an isolated place’)

So begins L’Histoire de Melody Nelson, with the narrator not in control; Not of the Rolls, or of himself, or of events. Melody Nelson, the 15 year old subject of the fourty-something narrator’s attention, will lose her virginity and then die as she flees home after their brief affair, the victim of a curse placed on the aircraft by the spurned Serge. This is how it must be. This is how it always was. Such a perfect beauty must perish.

Melody, track one of this story record, sidles in with an almost sickly, jaunty funk; it is a spare bass drums and guitar arrangement, loose and sauntering. When Gainsbourg’s voice enters, a low, resigned sigh pushed disorientatingly loud in the mix, it is an instrument that conveys the knowledge that it’s owner is himself but an instrument of the Gods. He is waiting for St. Peter’s verdict with little attention on the outcome, for he knows what it will be. This is a listlessness born of knowledge. It’s truly dangerous. He knows the handcart to Hell and Heaven follow the same dirty routes. His are spent forces. A man capable of a crime of non- passion. An Atlas who turned his burden in a ditch; a Hercules who is finished with his labour’s and still no closer to the end. He is tired of love in a way only romantics can be. He’s boxed too many rounds with those shadows, and knows the judges are bent. And from this position, we recieve the story of Melody Nelson.

Ballade de Melody Nelson, track two, is utterly sublime, with Jane Birkin as Melody finishing lines in that breathless smile of a voice, and slips by in two minutes; Valse de Melody and Ah! Melody, grander and sadder, are shorter than that. After the lengthy, meandering opening track, three gorgeous, out and out declarations of love disappear over the horizon in a blink. After the broody set up of L’Hotel Particulier, a downbeat string-led walk through the layout of the mansion where the narrator and Melody are going to find a room, the scene is set. Then, we are disturbed by a spazzy funk, and En Melody, the consumation of the romance, is jolly throwaway and all the more perverse for it. The only voice heard is Birkin’s as Melody, and she does not speak. She cackles a genuine cackle, and that death rattle of a laugh, is funny; and laughter is never funny. In place of a more earnestly romantic gesture, (like the swooning she did on Je T'aime...Moi Non Plus) this is a thumbed nose.

The tightrope between parody and melody, between love and hate, meaning and flippancy, is walked throughout Gainsbourg’s career, it’s his biggest strength, and it’s also what denies him entry into the pantheon (besides being witty in a foreign tongue). He treats pretty faces and petty faeces with equal import; high art with loud farts. And so the consumation here must be a cheeky joust, as Serge continues to drag us from the ridiculous to the sublime, becuase that is how life is with the fates, one huge joke at the romantic’s expense. In being contrary and perverse he personifies both why the English-speaking world has such disdain for foreign pop and why we are lazy fools. Expressions of confusion, emotional complexity or doubt are surely the most pertinent ones, and yet we repeatedly turn our backs. Sigh. Serge’s greatest hit, Je T’aime...Moi Non Plus could only get banned for being too raunchy in England, and then later become a symbol to us of sex-obsessed Frenchness, when in reality it is a send-up of the old-man-being-seduced-by-a-young-girl-yeah-in-your-daydreams macho-frolic, with sharp lyrics, as well as being a poignantly rendered romantic anthem in it’s own right (laughing, giggling together being the height of romance of course, you at the back). This means that it is, to these ears at least, the kind of have-your-cake-and-eat-it mind trick that only a particular streak of genius can fire. That’s the thing with the English. We think that because we’re funny that no-one else can be. And so Serge became the dirty old Frenchman in the country he least wanted to be, ours.

Love dies. Bogart offered Graeme too many embraces that smothered; displayed too many grabs and holds that conveyed murder and danger; doubts emerged, but they were doomed all along. There is no certainty greater than the certainty of killing one’s greatest love. The Rules mean that as it always was is how it shall always be. Bogart carried the countenance of a man who knew it and didn’t like it, but was powerless to stop it; the best that can happen under such sufferance is to find a sadistic pleasure in the self-destruction, the kind that Gainsbourg finds here, as he curses his love, destroys her and smiles oh so bitterly at his own failures.

And so the record ends with Cargo Culte, which musically is a retread of the opener, and repeats the introduction of Melody (‘Tu t'appelles comment ? -Melody. - Melody comment ? - Melody Nelson’). Hello as goodbye. Serge’s bitterly stinging, sweet hex on his love kills her, but he was God’s device. A heavenly choir sings, and we have the crescendo that has been denied for so long, an almost overwrought, parodic finish.

‘Les ailes de la Rolls effleuraient des pylônes

Quand m'étant malgré moi égaré

Nous arrivâmes ma Rolls et moi dans une zone

Dangereuse, un endroit isolé’

(‘The Rolls' wings brushed against poles

When despite myself off my path

We arrived my Rolls and I in a dangerous

Zone, an isolated place’)

So begins L’Histoire de Melody Nelson, with the narrator not in control; Not of the Rolls, or of himself, or of events. Melody Nelson, the 15 year old subject of the fourty-something narrator’s attention, will lose her virginity and then die as she flees home after their brief affair, the victim of a curse placed on the aircraft by the spurned Serge. This is how it must be. This is how it always was. Such a perfect beauty must perish.

Melody, track one of this story record, sidles in with an almost sickly, jaunty funk; it is a spare bass drums and guitar arrangement, loose and sauntering. When Gainsbourg’s voice enters, a low, resigned sigh pushed disorientatingly loud in the mix, it is an instrument that conveys the knowledge that it’s owner is himself but an instrument of the Gods. He is waiting for St. Peter’s verdict with little attention on the outcome, for he knows what it will be. This is a listlessness born of knowledge. It’s truly dangerous. He knows the handcart to Hell and Heaven follow the same dirty routes. His are spent forces. A man capable of a crime of non- passion. An Atlas who turned his burden in a ditch; a Hercules who is finished with his labour’s and still no closer to the end. He is tired of love in a way only romantics can be. He’s boxed too many rounds with those shadows, and knows the judges are bent. And from this position, we recieve the story of Melody Nelson.

Ballade de Melody Nelson, track two, is utterly sublime, with Jane Birkin as Melody finishing lines in that breathless smile of a voice, and slips by in two minutes; Valse de Melody and Ah! Melody, grander and sadder, are shorter than that. After the lengthy, meandering opening track, three gorgeous, out and out declarations of love disappear over the horizon in a blink. After the broody set up of L’Hotel Particulier, a downbeat string-led walk through the layout of the mansion where the narrator and Melody are going to find a room, the scene is set. Then, we are disturbed by a spazzy funk, and En Melody, the consumation of the romance, is jolly throwaway and all the more perverse for it. The only voice heard is Birkin’s as Melody, and she does not speak. She cackles a genuine cackle, and that death rattle of a laugh, is funny; and laughter is never funny. In place of a more earnestly romantic gesture, (like the swooning she did on Je T'aime...Moi Non Plus) this is a thumbed nose.

The tightrope between parody and melody, between love and hate, meaning and flippancy, is walked throughout Gainsbourg’s career, it’s his biggest strength, and it’s also what denies him entry into the pantheon (besides being witty in a foreign tongue). He treats pretty faces and petty faeces with equal import; high art with loud farts. And so the consumation here must be a cheeky joust, as Serge continues to drag us from the ridiculous to the sublime, becuase that is how life is with the fates, one huge joke at the romantic’s expense. In being contrary and perverse he personifies both why the English-speaking world has such disdain for foreign pop and why we are lazy fools. Expressions of confusion, emotional complexity or doubt are surely the most pertinent ones, and yet we repeatedly turn our backs. Sigh. Serge’s greatest hit, Je T’aime...Moi Non Plus could only get banned for being too raunchy in England, and then later become a symbol to us of sex-obsessed Frenchness, when in reality it is a send-up of the old-man-being-seduced-by-a-young-girl-yeah-in-your-daydreams macho-frolic, with sharp lyrics, as well as being a poignantly rendered romantic anthem in it’s own right (laughing, giggling together being the height of romance of course, you at the back). This means that it is, to these ears at least, the kind of have-your-cake-and-eat-it mind trick that only a particular streak of genius can fire. That’s the thing with the English. We think that because we’re funny that no-one else can be. And so Serge became the dirty old Frenchman in the country he least wanted to be, ours.

Love dies. Bogart offered Graeme too many embraces that smothered; displayed too many grabs and holds that conveyed murder and danger; doubts emerged, but they were doomed all along. There is no certainty greater than the certainty of killing one’s greatest love. The Rules mean that as it always was is how it shall always be. Bogart carried the countenance of a man who knew it and didn’t like it, but was powerless to stop it; the best that can happen under such sufferance is to find a sadistic pleasure in the self-destruction, the kind that Gainsbourg finds here, as he curses his love, destroys her and smiles oh so bitterly at his own failures.

And so the record ends with Cargo Culte, which musically is a retread of the opener, and repeats the introduction of Melody (‘Tu t'appelles comment ? -Melody. - Melody comment ? - Melody Nelson’). Hello as goodbye. Serge’s bitterly stinging, sweet hex on his love kills her, but he was God’s device. A heavenly choir sings, and we have the crescendo that has been denied for so long, an almost overwrought, parodic finish.

Labels: Music Review Serge Gainsbourg

1 Comments:

All can be

Post a Comment

<< Home