Because of the firework feeling in his bones, Uncle Robert knew our town was the dead centre of England. 'The reason I ended up here is because it is the middle of everything,' he said.

Many experts would have contradicted him. New surveys of the land came every other year or so and the officially recognised geographical bulls-eye would move, perhaps over the hill beyond Higham, sometimes several miles in another direction. Every place ever named as the centre of the country clung to the very verdict that put them there, and disregarded all subsequent alternative suggestions. They would display their achievements and wares at fetes and carnivals, festivals and parades. But none was ever more extraordinary than the next: Neolithic flint implements, Bronze Age Burial mounds, Roman coins and Saxon suffixes were regularly polished and shown, but to us children, being from the dead centre of England only meant we were further from the sea than almost anyone.

But Uncle Robert had moved to this town as if drawn by some magnetry. And he knew it was the dead centre of England. He walked its contours, plugged himself into its vagaries, soaked up its airs. He pressed the claims of our town in varied ways. 'Have you ever noticed that our train station is far bigger than we seem to deserve or need?' he'd say. 'It is, in effect, a staging post for travellers on a journey through the middle of England, usually from South-East to North-West and back. It’s a route which is a well-set series of wires and arteries that carry fortune seekers, commuters, noise, spite and other cultural exchanges. Look on a map: Britain looks like a wounded man, leaning to the west; it’s the weight of it, that lopsided pull, with everything in the South-East, and something in the North-West, and everywhere else slipping into the wind. And it all comes through here. No matter what they say, this town is the dead centre of the country. That station marks the spot, I’m sure. You can feel it.'

According to Uncle Robert, trains were the lifeblood, the force, angels of fate to take you or usually in our case, leave you behind. They were cartographers of the invisible land; following the best taken path, preselected above man's input, along routes that predated even the tracks. Rivers meander weakly to sea, but train tracks, like roads and shipping lanes, chose themselves. He said if you build a track where it doesn’t want to go, there’ll be an accident sooner or later. 'The sinking of the Titanic proved that you can’t build a track over the North Atlantic, so we should never try. Man hasn’t the power to guide a machine down a set path. A train is actually pacing out the perimeters of nature’s power. Rome, for example, didn’t fall; it was pushed, by men who believed their petty transactions put them in Godly positions. Their folly was not ambition, but that that didn't listen to the land. If you could read the roads and lines, look for accidents as signs, you’d see how the trains tell who did it; With sensitivity, you could plot lines that would circle the truth like Injuns round wagons, they'd be driving gutters into the Earth, grooves of repetition that would bore into the earth and bore the surrounded to death.'

That’s how he'd talk. Mum said he was an Idiot's Haven't. I loved him.

We'd go to the station together, Uncle Robert, his son Tony and I, and watch as trains swung into our town and were thrown out to bigger destinations- Northampton, Birmingham New Street, Liverpool Lime Street, London Euston. We’d watch the faces as they waited to move on, drowsy disinterested abstractions through glass, like timid sketchbook preliminaries. We'd wonder how they stayed so uninvolved in the process, in the glory of travel; Uncle Robert who had travelled, and explored, and Tony and I who longed to.

While the people on the train only ever passed through, Uncle Robert had thrown his fate in with that of the town. And even though he’d come from elsewhere (and still had his busty dialect to show for it) the town seemed to respond to him, as if it couldn’t help it. The events in the town's life intertwined with his. He was born in the year they built the Old Hall, what we knew as the Co-Op Hall. That was a totem in these parts, a landmark that announced itself in an area whose qualities generally had to be coaxed and teased out. For a period, it was the only place to choose for wedding receptions. One New Years Eve, just after the war, some guests slipped on the stairs and several were killed in the crush. That was the same night that, miles away in Leeds, Uncle Robert's father was run over by a car.

Uncle Robert moved to town shortly after marrying Joan in the year they built the ring road, 1972. That road breathed life into new directions, and the Carters lived in a small house up past the hospital, a little hutch that years later we’d drive past and observe like a cute relic; diverting, langourous drives home they were too, and to see Uncle Robert see the first matrimonial home was for me one of the earliest examples of stirring nostalgia. 'The first morning we lived there,' he'd tell us, every time, 'I woke up, stretched, kissed my new wife, and turned to see on the pillow... well, you'll never guess what.'

'Your hair!' we'd chorus, amazed not by the fact that Uncle Robert's hair fell out so quickly but by the fact that he ever had any at all. He lost his front teeth when his first child, Tony, was born, but it wasn’t an incident touched by the supernatural; a combination of celebratory gins and steepling maternity ward staircases saw to them.

He smelt of Vicks and whisky, both of which were always medicinal; he’d give us a nip when we’d twist an ankle, dab both on a grazed limb, and we’d gaze at the bottles together in awe. 'Learned the power of these in King's Gym in Huddersfield in the fifties' he'd say with a wink.

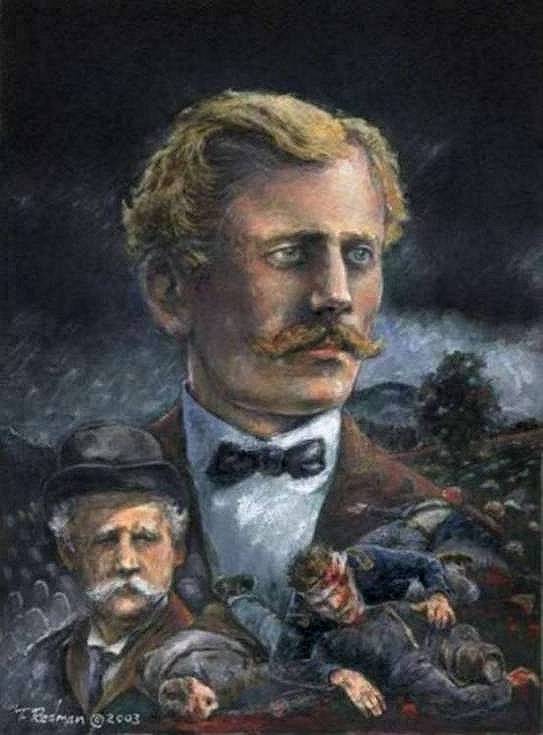

Uncle Robert had been a boxer, but he drifted into wrestling in the lean years, when his honest nose had been crushed one too many times by sly jackhammers that evaded his aging defence. He clearly thought that wrestling was the lesser art, glistening as it did with cheapening pizzazz and silly non-glamorous display, but instead of getting frustrated, or looking elsewhere, he took his opportunity, and brought all his disdain for the tawdry flash of the sport into his role of the villain up at the Co-Op hall for years. He was a good sport, but disliked being forced into uncompetitive surrenders and premature dives by the demands of a crowd and their collective wish, and expectation, of a vengeful pantomime in which the villain cheats the hero and is thus punished. Despite his reservations, he had a surprising knack for increasingly creative acts of dishonour in that ring, and this endeared him to one and all, who, apoplectic at the referee’s distractibility, would bellow a warning to the dazed hero as Uncle Robert approached the groggy saint from the rear with a piece of wood or sandpaper.

Tony and I experienced these bouts only through Uncle Robert's retelling of them. We were too young for the rowdy environs of a wrestling evening, and could only superimpose his actions onto the more family-friendly visions conjured on our television on Saturday afternoons. We insisted, in our giddy re-imaginings in the garden, that the Uncle Robert could trouble not only Les Kellet, Mick McManus, Jackie Pallo, Steve Veidor, and Tibor Szakacs, but would despatch of Count Bartelli, dethrone The Royals, and destroy the smiling, handsome Johnny Saint, who we hated.

Uncle Robert's alter-ego for many years was The Tarantula. His costume consisted of red vest, red trunks and a balaclava-style mask. He had cobwebs painted in silver on his back, but didn't look like a spider. He'd let us play in the costume, one of us tripping over the trunks and vest, the other swallowed by the mask, but we rarely did, just handled it with delicacy, feeling the weight of it's hem and the gritty sparkle of the logo. 'That old thing. My straitjacket,' he'd call it, smiling. The stories were painted in by his chuckling recall. Tony and I would always cheer on our man on as he told us the tales of those times; dreaming we were there, when The Tarantula fought against the course of the crowd and the wishes of natural order.

‘The younger lads, the goodies, they’ve got to win, you both know that,’ he’d say, and we’d nod, sure that Robert would have been the greatest hero of them all if wasn't all rigged against him. The villains interested us, and there always seemed to be new ones to tell us about. The Valkyrie, a screeching sneak who The Tarantula sometimes teamed up with, a melodramatic former child nearly-star (he’d been on the stage in the war years as the bombs rained on Coventry) who wound up dead from the booze in his caravan up the A5 years later. Pirate Pete, a man who was larger than Giant Haystacks, kept puppies in his yard and could lift a mini over his head. The Mysterious Shadow could shin up a lamp-post with his hands tied behind his back, and had a cafe in town for a while before he died. We'd visit and have a bowl of ice-cream, and The Mysterious Shadow would playfight with Uncle Robert for our benefit.

'We're old now,' they'd say when we got too excited. But they fondly recalled how in the nineteen-seventies they created a merry Valhalla, stirring up boisterous crowds in gym halls, clubs and pub backrooms all over the Midlands.

Uncle Robert had his first wrestling bout at the Co-op hall in 1975. The ballroom itself had died a series of squalid deaths over decades of mismanagement, its dignity slipping and trodden into the dirt with every transformation; from celebrations of blessed unions, to ballroom dances, to bingo, wrestling, before being crushed under heel when they painted the interior black and turned the place into a grubby arcade later in the nineteen-eighties. One rainy Saturday afternoon when I was twelve a girl I didn’t even really like refused to let me kiss her there. But that night in 1975, the night of Uncle Robert's first wrestling bout, a London to Glasgow train came off the rails down by the Leicester Road Bridge, dragging up track and dirt until it came to rest on the platform, taking down part of the station roof and thirty-six souls. Uncle Robert joined the volunteers while still wearing his wrestling leotard, and blackened and thirsty, lifted rubble and twisted iron with them all night like some mythological Colossus, rueful and black.

Within a couple of years, Uncle Robert was an established name on the wrestling circuit. When the Scala and Grand cinemas both closed, there was an upsurge in popularity for the events. The Tarantula started a long rivalry with a foppish lad of upstart vulgarity, who would run through Uncle Robert’s legs. The Wasp, as he was known, was a gypsy of Italian origin whose family had come from Naples, and Carter and I would later know him as the elderly drunk who ran the sticky dodgems at the fair. In his younger days he was darkly handsome, a preening stud who the crowd adored. We knew only his slobbering approaches to teens of all genders on August Bank Holidays as the fair struck up for a last night.

Uncle Robert would tell us that he’d have to pretend not to be able to catch the greasy little Wasp, and would wink to Mrs. Carter and baby Tony in the crowd, and Tony Carter would say he remembered all this, even though he couldn’t have been more than one or two. Uncle Robert would have to pretend that the little Italian was too quick for him, and sometimes, he chuckled, The Wasp was too quick, and he didn't need to pretend at all, by that point being almost forty and overripe. By the time the Palace theatre had closed and there had been a murder down the back of the Ringway the following November, Robert had broken a leg when pinning a man from Derby (Gorgeous Geoff or Sid the Saint, depending on what day you were told the tale), a blessing of sorts, in that it gave him the shuffling limp that would give him a new name in the twilight years of his career, The Crab.

And then near the end we got to see him wrestle.

We were nine. It had been a while since Uncle Robert had been bouting, and he was roped out of retirement, he said, as a favour to an old promoter. I think he did it so that Tony and I, so thrilled by the stories, could see one played out in front of us for real. Aunt Joan, never a fan, reluctantly took Tony and I, and we all drove up to Leicester together. She tutted at the language, winced at the dusty aroma, choked on the smoke, but Tony and I stared at it all with wonder. Uncle Robert's tales may have glamorised the settings somewhat; the beery squalor and shabby ring were not what we'd expected; but to us it was the height of exoticism. We were amongst men after dark.

It was the only time I saw the old boy fight, and it was his last time. And he won, ignoring the script to pin some young upstart. He winked at us as he did a lap of honour, and we knew that he'd done it for us. It was to be his last fight.

It had to be the end, because his body wasn't up to it anymore. A couple of months previously, on the coldest night on record in our town, -22 degrees, January 1983, Uncle Robert had ripped something in his shoulder. Though this added to his villainous lean, meaning that the Crab walked more convincingly lopsided than ever, he couldn’t grapple anymore. He soldiered on a little, defiantly, and his last bout in town, a couple of months before the Leicester trip, was the same night they closed down the Ritz for good and converted it into the bingo hall. ‘The last film was ‘Blood Bath at the House of Death’. ‘It was a terrible British comedy,’ he’d say, ‘what a send-off.’

At the end, he was sad to leave. He’d toiled and entertained, achieved minor regional fame, and drew lessons from his experiences like a serum.

‘Wrestling is a medium of truth to us Brits.' he'd say. 'Its essential narrative is about right and wrong. It acknowledges failure. That’s something the Yanks won’t ever get. They think that winning and being right is the same thing.’

And then one day he slipped away after a heart attack aged fifty-four, the same night as the town’s most famous modern son, a light entertainer known to the nation through Saturday night television died. I was away on a school trip, and they didn't tell me until I got back, didn't want to disturb my break. I missed the funeral. Aunt Joan and Tony moved away shortly after that, and continued to move over the years, their radars threatened and confused in his absence. Indeed, not long after he died, there was a survey using new technologies that placed the dead centre of England some twenty miles away. This was the biggest variation I could remember, and subsequent surveys, powered by the precise mathematics of new systems, never remotely came close to suggesting our town was the centre of England again. It was as if Uncle Robert's death had thrown the country lop-sided, never to sit true again.

‘Be careful,’ he said to me once. ‘A good man’s only got twenty years of running in his legs. After that he’s a shadow, living off what he’s done. An early starter like you, he might only have nineteen years, seven, eight months left, give or take a couple of days. You should be writing books. But you’ve only got a certain time, a little noise window. Nineteen years of books in your legs, if you’re blessed.’

I nodded vaguely, and looked out across the garden night. A cheese of a moon was rising into somebody’s birthday.

‘Don’t sleep too much son’ he said, and raised an arm to ruffle the hair behind my ears. As he disappeared into the patio doors, I called him.

‘Have you ever written anything?’

‘Of course not.’ he laughed, as if it was the first time he’d considered it. ‘Waste of time.’