FIME FUNNEL

'Time is not a darkened tunnel. Time is but a blocked up funnel.'

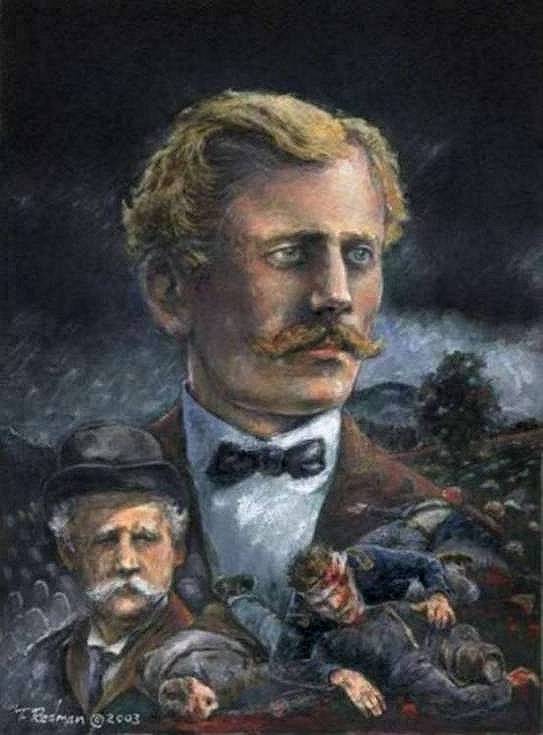

In which Great-Uncle Dylan-Savage settles a modern predicament with Victorian-era words!

Writing in 1894:

'In these days, a heady nation finds itself awash with nostalgia for it's past successes; We not only have resplendent pensioners reminding us of the potency of the Great Exhibition over four decades ago, but we see 14 year-olds pining for the time, now subjected to history, when they were but befreckled eight-year-olds living in fear of the very active Ripper in London's grotty Eastern ends!

By the end of the twentieth century, I suppose that adolescence will have stretched, meaning that females of thirty will not be married! And nostalgia will have exploded, meaning that pre-teens will relive in some advanced photographic contraption, the glory of their toddlerdom, and profess to feeling aged and haggard, all at but nine years old! Every person in the land will thus simultaneously see himself as old (with a long past stretching ever backward) and young (with more leisures to come). This I suggest we call the Parallel Paradox, or the Growing Down Stratagem, or somesuch snappy title. I am as much a victim as any other to this condition: I've mourned epochs I never knew; gnashed my teeth over unrequited love with dead strangers I've never met, our eras being separated by millennia. This self-regard is terminal. Might we one day spawn children who cry at birth because their wombic pasts are lost?'

Ah. When Great-Uncle Dylan-Savage speaks, the sound of tacks being struck across their bonces fills the room. For further evidence, see previous posts for trails of his particular artistic inquiry and slithery genius. Great-Uncle Dylan-Savage begets this blog, and the world.

Me? I vividly recall walking to a professional photography studio with my Mum, Dad and sister, not long before my parents' divorce. I remember my seven-year-old brain attempting to store the details of every drain and brick along the way, because I wanted to force my future self to hold onto that moment. I was completely aware at the time, not only of the fact that I would grow old and big many years from then, but that I would look back on my childhood with curiosity and wonder. This awareness threw a gauze over the whole day: As I posed with my sister in front of fictional rural scenes and smiled for the photographic record, I experienced a detachment from bodily goings-on; I was watching my own nostalgia being invented and shaped at that moment, budding and stretching for air, to return decades on. Perhaps some vague awareness of the impending separation of my parents sparked it. Looking at the photographs now, I do not see any obvious signs of the immense self-awareness I felt; There is no I-know-it's-a-dream glint in my eye, no glistening effervescence that is greater there than in any other childhood pictures. But that day, I was acutely aware, perhaps for the first time, that I myself would be looking at these pictures sometime in the future; I could see, immeasurably and uncannily, the timeline of my own life, and how it knots and loops.

My life up to the point of those photographs is a series of semi-fictionalised artefacts (eating a garden snail; pulling on a stranger's ears and shouting 'Na-Nu, Na-Nu!', autistically creating elaborate lines of toy cars) smoothed by repeated retellings at family Christmases to smooth, hard pebbles, identical in everyone's mythical imagination, even (perhaps especially) those that weren't present. As I'm known as the kid who was good, any bad behaviour is forgotten.

Since then, I've always been aware when I am dreaming. It causes me to laugh at the unreal threat of nightmare dreams and be absolutely depressed by the illusory magic of happy ones.

In which Great-Uncle Dylan-Savage settles a modern predicament with Victorian-era words!

Writing in 1894:

'In these days, a heady nation finds itself awash with nostalgia for it's past successes; We not only have resplendent pensioners reminding us of the potency of the Great Exhibition over four decades ago, but we see 14 year-olds pining for the time, now subjected to history, when they were but befreckled eight-year-olds living in fear of the very active Ripper in London's grotty Eastern ends!

By the end of the twentieth century, I suppose that adolescence will have stretched, meaning that females of thirty will not be married! And nostalgia will have exploded, meaning that pre-teens will relive in some advanced photographic contraption, the glory of their toddlerdom, and profess to feeling aged and haggard, all at but nine years old! Every person in the land will thus simultaneously see himself as old (with a long past stretching ever backward) and young (with more leisures to come). This I suggest we call the Parallel Paradox, or the Growing Down Stratagem, or somesuch snappy title. I am as much a victim as any other to this condition: I've mourned epochs I never knew; gnashed my teeth over unrequited love with dead strangers I've never met, our eras being separated by millennia. This self-regard is terminal. Might we one day spawn children who cry at birth because their wombic pasts are lost?'

Ah. When Great-Uncle Dylan-Savage speaks, the sound of tacks being struck across their bonces fills the room. For further evidence, see previous posts for trails of his particular artistic inquiry and slithery genius. Great-Uncle Dylan-Savage begets this blog, and the world.

Me? I vividly recall walking to a professional photography studio with my Mum, Dad and sister, not long before my parents' divorce. I remember my seven-year-old brain attempting to store the details of every drain and brick along the way, because I wanted to force my future self to hold onto that moment. I was completely aware at the time, not only of the fact that I would grow old and big many years from then, but that I would look back on my childhood with curiosity and wonder. This awareness threw a gauze over the whole day: As I posed with my sister in front of fictional rural scenes and smiled for the photographic record, I experienced a detachment from bodily goings-on; I was watching my own nostalgia being invented and shaped at that moment, budding and stretching for air, to return decades on. Perhaps some vague awareness of the impending separation of my parents sparked it. Looking at the photographs now, I do not see any obvious signs of the immense self-awareness I felt; There is no I-know-it's-a-dream glint in my eye, no glistening effervescence that is greater there than in any other childhood pictures. But that day, I was acutely aware, perhaps for the first time, that I myself would be looking at these pictures sometime in the future; I could see, immeasurably and uncannily, the timeline of my own life, and how it knots and loops.

My life up to the point of those photographs is a series of semi-fictionalised artefacts (eating a garden snail; pulling on a stranger's ears and shouting 'Na-Nu, Na-Nu!', autistically creating elaborate lines of toy cars) smoothed by repeated retellings at family Christmases to smooth, hard pebbles, identical in everyone's mythical imagination, even (perhaps especially) those that weren't present. As I'm known as the kid who was good, any bad behaviour is forgotten.

Since then, I've always been aware when I am dreaming. It causes me to laugh at the unreal threat of nightmare dreams and be absolutely depressed by the illusory magic of happy ones.